Chris Arnett interviewed on CBC Radio: 23 February 2008

Historical Society Presentation

TwoHouses.001.jpg

TwoHouses.001.jpg

TwoHouses.002.jpg

TwoHouses.002.jpg

TwoHouses.003.jpg

TwoHouses.003.jpg

TwoHouses.004.jpg

TwoHouses.004.jpg

TwoHouses.005.jpg

TwoHouses.005.jpg

TwoHouses.006.jpg

TwoHouses.006.jpg

TwoHouses.007.jpg

TwoHouses.007.jpg

TwoHouses.008.jpg

TwoHouses.008.jpg

TwoHouses.009.jpg

TwoHouses.009.jpg

TwoHouses.010.jpg

TwoHouses.010.jpg

TwoHouses.011.jpg

TwoHouses.011.jpg

TwoHouses.012.jpg

TwoHouses.012.jpg

TwoHouses.013.jpg

TwoHouses.013.jpg

TwoHouses.014.jpg

TwoHouses.014.jpg

TwoHouses.015.jpg

TwoHouses.015.jpg

TwoHouses.016.jpg

TwoHouses.016.jpg

TwoHouses.017.jpg

TwoHouses.017.jpg

TwoHouses.018.jpg

TwoHouses.018.jpg

TwoHouses.019.jpg

TwoHouses.019.jpg

TwoHouses.020.jpg

TwoHouses.020.jpg

TwoHouses.021.jpg

TwoHouses.021.jpg

TwoHouses.022.jpg

TwoHouses.022.jpg

TwoHouses.023.jpg

TwoHouses.023.jpg

TwoHouses.024.jpg

TwoHouses.024.jpg

TwoHouses.025.jpg

TwoHouses.025.jpg

TwoHouses.026.jpg

TwoHouses.026.jpg

TwoHouses.027.jpg

TwoHouses.027.jpg

TwoHouses.028.jpg

TwoHouses.028.jpg

TwoHouses.029.jpg

TwoHouses.029.jpg

TwoHouses.030.jpg

TwoHouses.030.jpg

233_Arnett_Two-Houses_CBC-Interview.mp3

otter.ai

17.04.2023

no

Speaker 1 0:00

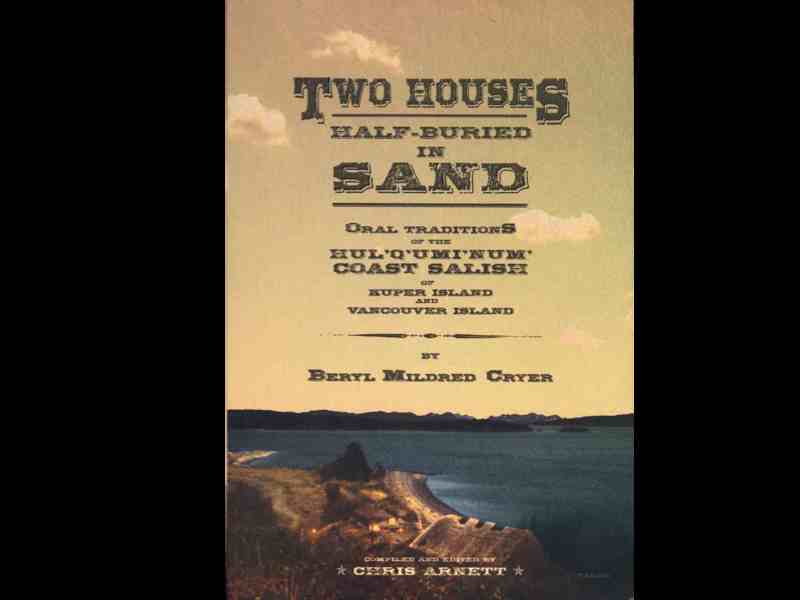

Hello. And Chris Arnett and I've been enjoying Christmas book for the past few days. It's a book entitled to houses half buried in sand and it's a book with a fairly complex genealogy. Chris discovered or rediscovered the writings of Beryl Mildred Cryer from a series of articles published first in the Times columnist in the early 20th century. And they were based on interviews that she had done, Chris, good morning. Thanks so much for being here. Thanks for having me. Tell me about about this. This research this this the interviews that Beryl was doing that have appeared in the pages of originally the Times columnist, and now in your book?

Speaker 2 0:39

Yes, well, barrel crier. Her maiden name was barrel Hall hood. She was the daughter of some well off upper class British immigrants who came and settled in the town of chumminess in the late 19th century. So she grew up around a privileged background, you know, an upbringing in shininess, you know, lots of parties in the tennis courts and, and all this but she also came into contact with a lot of members of the Native community, some of whom worked in the hall had household and so she grew up and married a local man, William Cryer, who was a local store Keeper and chumminess and, and began a family but depression came around and she was always looking for work and that and she was the society columnist for chumminess for The Times columnist and then these are

Speaker 1 1:36

not the society columns that are in this book. No, no, but she was so she was offered a job with

Speaker 2 1:40

the with the Times columnist who writes stories about Native history for the Sunday magazine and it became very popular and so she contributed for over three years. And you might

Speaker 1 1:53

think on hearing that somebody who used to write the society column and somebody who was from that kind of a background that these these stories could be very superficial or are not at all important, but obviously you don't think that at all.

Speaker 2 2:07

Well, that's the remarkable thing about her she one of the major storytellers in the book is a woman named Mary Rice, who lives in a cabin by the hall at home and so as a girl grow up, was growing up she befriended Mary Rice, who was a you know, an awesome, great storyteller in a traditional culture bear of the, the Huntington speaking people. And so she was sort of schooled by the best and but she also had a natural ability as a writer and you know, real love for the people and was able to convey it in her writing. And the remarkable thing about her is that she preserved the voice of the storyteller without paraphrasing, and which is significance? Yes, very much so because anthropologists of the day often male anthropologists use usually paraphrased other information and, you know, even less of the names of the informants whereas verbal, you know, identifies these people by their English name and or Indian names, which is really significant. And, you know, and she paints a picture of them as well. Yes, she's she was very good at you know, describing their personalities and so you get a real sense of the storyteller and the person and the individual who tells the story,

Speaker 1 3:23

and many of these stories, I think, would not be necessarily with us these days if barrel had not written them down. Yeah, absolutely.

Speaker 2 3:30

The native people in 1927, the federal government outlawed any sort of research into native history. And this because land claims was a big issue in those days. And I think there was a there was a feeling in the native community that here was this woman who could convey their stories to a greater public because when you read this the stories, it's very evident that the people wanted their stories to be told, and they wanted them, you know, to reach a wider audience so that people would understand the history of this place.

Speaker 1 4:03

I didn't treasure when you were Richard, researching in the archives, what was it like for you to come across these newspaper articles and begin to realize what was there? Well, it was

Speaker 2 4:12

really exciting because, you know, a lot of the stories you know, resonated with me because I I, you know, heard heard them from other elders, you know, that I've worked with and and the Yeah, they just, you know, these stories that you know, had been sort of buried.

Speaker 1 4:33

It seems me too, when I think about I mean, it was her dream during her lifetime, as you mentioned, that these would be published in a book, which, unfortunately, didn't happen. But now I think of you living here and part of your background is Mallory, and beryl, who was not First Nations, and yet, somehow in this wonderful collaboration between the two of you, bringing these First Nations voices, we can enjoy them again. Yeah, it

Speaker 2 4:57

was a real privilege and it's kind of fun. It's come full circle because I first found her work. Right next door here in the provincial archives and a bunch of boxes they were just a yellowed newspaper columns taped on two pages, a full staff with no dates, no information, I wasn't even sure where they come from. But over the years, you know, I put it all together.

Speaker 1 5:17

That time is so limited. This always happens with with the shows that we have an audience and so much going on. But I just wonder if if there's a tiny sample you could read where we get a sense of of barrels voice and the voices of the people for whom she's transcript from whom she's transcribing the stories. Sure. Well, I

Speaker 2 5:33

could read this. The section from this was an interesting interview because it's Mary rice and her brother Tommy PL actually went and sought out barrel prior to tell her the story. It's a an article about salaries placings? This is Mary rice talking. First I'll tell you about the name Panella heads. That name means to logs have covered with sand longer ago than I can tell you there were no people living in this land. Then the sun made a few people on here on there in different places. But remember, they were not big and tall. The first men and women were very small like this. She held up a mummy like some well as I told you, there was no one on Cooper Island only the birds and animals. But the island look just as it does today. At the north end was that long points that makes one side of a bay at the head of this bay upon the bank. It was a spring of nice water coming right up out of the ground. And by that spring were two great cedar logs lying on the ground and have covered was sand washed up by the waves when the water was high. I don't know how many years was logs had been there was only the birds flying near and the animals coming to drink at the spring. When one morning the sun was shining down also hot. It shone down on these two logs and they got hotter and hotter. A maple tree was growing here and it gave a little shade to one of the logs. But the other one was right out in the sun by the bark and this log began to crack. And soon he began to move is there something in the log was trying to come out? Suddenly there was a lot of crack. The bark split open and up came a little man he crawled out of the log and sat in the sun getting strong. Now the water was far up that morning. And as the sun got hotter and hotter, the sun got very hard and dry. And as little man sat up on his log watching the sun drying up the water. He saw the sand between the two logs open just as the bark had done. And out of the sand came a little wouldn't.

Speaker 1 7:32

You'll have to read the book to find out what happens next. at that critical point. Chris, I'm going to have to stop you right there. Chris, thank you so much. Thank you for doing the research. Thank you for making this book available. So we have a chance to read it I have certainly been enjoying reading it these past few days and will continue to do so. And the book is published by selling books Talon books thanks to Talon books as well. Chris Arnett and two houses have buried and Sam thank you so much for being here this morning.

233_Arnett_Two-Houses_Historical-Society-Presentation.mp3

otter.ai

17.04.2023

no

Speaker 1 0:00

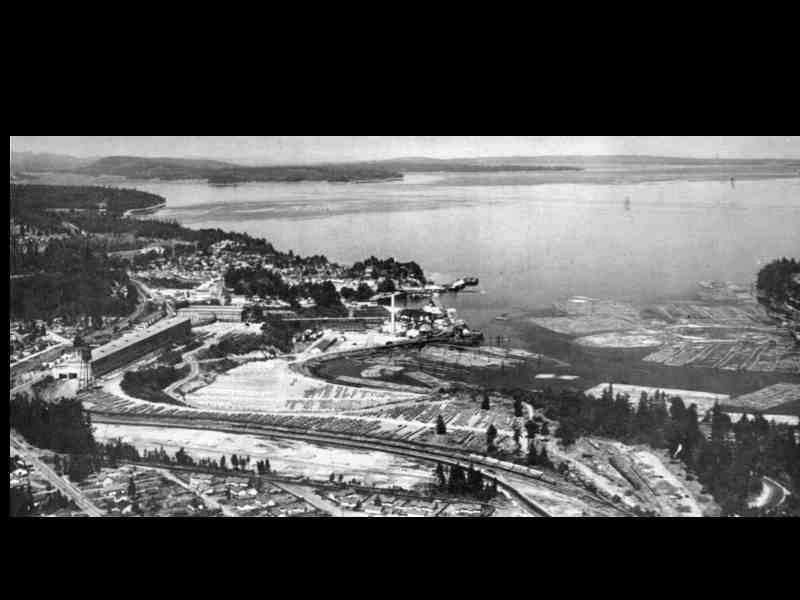

So today I'm going to talk about a book that I just I just or talent books just published a collection of writings by barrel Mildred crier and on the oral traditions of the hall coming from Coast Salish, and it's a book I've been working on for about 10 years, I came across her work in the provincial archives when I was doing research on an earlier book of mine, a terror the coast. And I discovered this stuff in three archival boxes, they were undated newspaper clippings all yellowed and taped to pieces of full staff. And I said, What's this, you know, and I didn't know where they were from, or who or who wrote them. And as I started to read them, I was first put off by the journalistic style, you know, being a serious historian and all it kind of, you know, was taken aback but as I started read the stories, I realized that this was really important material, and it resonated with a lot of research I'd been doing with First Nations people and, and various archival research, but it was just fascinating stuff. And so I, you know, photocopied all of it, and use some of it in my book, The Tear of the coast and over the years, I've always had this dream of publishing it and, and barrel crier, you know, wanted to have this material published during her lifetime, but was never able to accomplish it. So I feel very privileged to have finally been able to help her bring these stories out from the ephemera of the newspaper to the printed book version. I call the two houses have varied insan sort of a metaphorical allegorical title. Referring to the the collaborative nature of the book, the collaboration being barrel, Mildred crier, who was sort of an upper middle class British background, and her informants, so people that gave her the stories, who comprised 15 Coast Salish elders, from Nanaimo cucur, Island Cowichan, and other places Galliano Island and the stories you know, originally were given an ultimatum, which is the, the ancient language of this place. But they were given to barrel Mildred crier in English and all of these people, you know, the most of them were born in the 1860s. And so they, they'd grown up with the English language and they were fluent in it. So that's part of the allusion to the two houses and the house, of course, is the greatest political unit. In the native village, you can see a picture of a house here. This is a photograph of an elephant on Cooper Island, half buried and sand is a is a reference to the village of Panella huts, which we see here in this picture, a photograph I took in 1983, showing the last standing longhouse on the beach, originally 15 of these structures along the beach, each one housing, an extended family. This was the last one standing that blew down about two months after I took this photo. And the name Panella sets refers to the condition of houses being very half buried in sand because as you approach this spirit from the water in the sand is sort of blown up against the sides of the houses and it looked as though they were kind of half buried in the sand. So and also half the stories in the book are from Cooper Island, which most of you know or should know, is the island or Island neighbor just to the north of us. Are you gonna point in that thing, okay, that the Hawk can eat them, which is the reference in the title. This these are the this is the language spoken by the people that live in this area. You can see on the map, they lived between the noose Bay and the North to around Malahat and Holcomb it is a dialect of the greater Holcomb Eylem language which is spoke from this area all the way up to hope all the way up the Fraser Valley and has many different dialects. You can see some of them here all these little segments are different dialects of the languages. But linguists now are beginning to think that coming in, which is only spoke on the east coast of Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands has sort of reached a status of its own language. And it is very similar to the mainland Holcomb Eylem. But there's a lot of sound shifts, and there's a lot of different words. And so yeah, it's it's a distinct language. Unfortunately, there's only about 100 fluent speakers today, and maybe 300 People who are partially fluent, but things are changing, you know, they they there's a program and place amongst the couch and tried to revive the language. And they finally got to a computer friendly way of spelling it those of you who study English or Indian languages, you know, it's been In the hands of linguists for so long, they've upside down sevens and backward letters. I mean, nobody can read this stuff. But now the couch and tribes have developed a computer or a keyboard friendly way of writing language. So I think it really bodes well for the preservation of language. And here you can see the three main dialects of welcoming them, which Nanaimo chumminess and Cowichan install the stories in this book is about 60 stories all originated from this area. Still has anybody here are very well, like, some of you may have heard of this language Shinnok. And people say, Oh, this schnuck was this lingua franca that everybody had to learn. So they could communicate, this is false. Shinnick was invented by non Indian speakers for the purpose of communicating with Indian people because they, you know, it was too hard to learn the Indian languages, native people learn each other's language. It's the same way. Europeans, you know, someone who lived in Germany would learn French and Italian, you know, they, they were quite proficient in learning each other's languages. Chinook was, you know, a white man's invention. This is the village of Panella, which we saw on the cover the book, which is at the north end of cheaper Island. I forgot to mention the whole convenience people, you know, they have a long tradition up until only you know, as recently as 1950, archeologists, Western trained scientists believed the native people had only lived on the coast here for about 500 to 2000 years ago. But since that time, just in the last 50 years, there's been a lot of archaeological work. And they've pushed back the boundaries to about 8000 years, the oldest archaeological, the oldest dated site in the Lower Mainland is on the Fraser Valley, at the Glenrose cannery, and it's 1000 years old. And I'm sure that there's a lot of older sites in this area, we could, I think we could confidently say that people have been living in this area for 10,000 years. And these people, the culture that was encountered by the first white explorers, who was the was the product about 5000 years of continuous development, beginning with the stabilization of sea levels and whatnot, and the creation of clam beds and, and annual salmon streams, we have the development of the what they call the Coast Salish culture. And these people, like the political units were based on families that occupied you know, these large houses and this would be a political unit and then the house next door would be a separate family and they would have connections with families all over the area on different islands over on the mainland down in Washington State. In the interior, they had widespread networks of families, and this was done to provide greater access to the seasonal exploitation of resources, which was the basis of their economy, you know, that the annual runs of salmon on the Fraser River, the seasonal coming and going of nature, they had a very sophisticated elaborate, you know, technology to deal with the procurement of this stuff, which led to you know, quite a quite a good life over the millennia Oops. Okay, getting to Vail, Colorado. This is the town of chumminess on Vancouver Island, which most of you know about.

Speaker 1 8:27

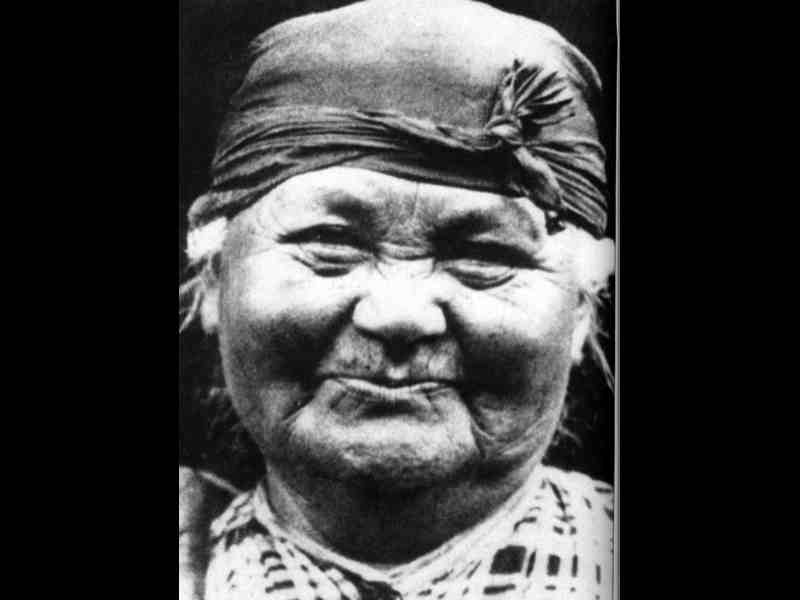

I just want to point out here, the word chumminess is based on the Indian village up here the whole community and village known as submenus Salinas, which means something like bite out of the breast, which refers to the the indentation of polluted Coogee Bay. So the original set semanas is up here. And when the whites first came to this area, they settled in, they actually established the first sawmill on East side of Vancouver Island right in this bay here was called Horseshoe Bay. And it's a fella named ask you to build a mill there in 1862, with a great waterwheel and so it was Horseshoe Bay, but over the years, you know, the name of Simonis, which was a large village here, it's still there. It's the largest Indian reserve in the on the east side of Vancouver Island. Gradually the name of you know became dropped into the name chumminess So this area became known as chumminess and the ASCII mill in 1862. was the first before mills and here I think is the latest version. There were four great lumber mills on this site. This is where HR McMillan sort of got his start when he took over the ban Victoria lumber manufacturing company, and over the years, you know, the middle just grow bigger and bigger and it's always been a mainstay of the chumminess economy. Now the barrel crier collected these stories from the native people in this area. Her fat She came from a family called haul EDS, and they moved here in the 1890s. Now in the 1890s. To me this was in the middle of A huge boom. Not only did they have one of the largest lumber mills in the British Empire operating down here in the harbor, the Copper Mountain mines on Mount Sychar were happening. The Croft and smelter was in full, you know, going full bore. And so it was a really booming time for this area. And this is when a lot of people moved here from sort of upper middle class ancestry from Britain particularly moved to Vancouver Island to you know, just you know, start off a new life in a in a so called new land. And the hall heads came originally to Victoria but ended up settling down here and purchasing about 50 acres on on chumminess Harbor on a large house that stood here on the edges of the harbor, but it's now covered over by the ever expanding mill operations. This is a hall had family and the hall heads came from horrible den near Canterbury in Kent, England, and they're from an old established British family and they had very close connections to the East India Company. So, you know, well off, folks, and this is an interesting picture. This was taken in 1910. They originally, as often happened in England, you know, the, these sort of landed landed gentry, these large families had lots of sons and only one son could inherit the family mansion, and the rest of the sons are sort of given a stipend and sent off to various parts of the world. So this son Richmond here, was sent to he and his wife, Gertrude went to New Zealand in the 1880s, where they had two sons. One of them's here, Frank and Arthur, and one daughter, Darrell, who was born in Auckland, New Zealand in 1887. With the death of Richmond's father, they returned to England inherited even more money from the estate. And then Richmond decided that the family would move to British Columbia, because if you study the newspapers in Europe, in the 1890s, there was a lot of publicity about BC and Western Canada. It was very attractive to people all over the world. Actually, the Dion's that were mentioned earlier, were part of this wave of sort of wealthy, upper middle class people, families that moved to this neck of the woods. So they came here in 1890, settled and Janina Stroud at 90 and had another daughter Maisel and Richmond here was appointed to be a constable in the British Columbia police force. So he was sort of the head constable which Manus and took on the duties of a policeman. Because they were members of the sort of the the upper class they, you know, created the first tennis court and Gimenez and they had lots of parties. Gertrude here was always organizing events. He was a musician and organized an annual hospital ball to raise money to create a tremendous his first hospital so they're very much involved in the sort of the the social activities of humaneness, especially associated with the Anglican Church of St. Mark's, or is it st angels, the church anyway, in Gimenez and Richmond here had a very famous cousin, Lord Baden Powell, who's shown here, who was of course everybody knows is founded the Boy Scout movement, and he was a frequent visitor to their estate. And they had quite an estate, they had a big house, tennis courts, a giant picnic table, that's, you know, seated 100. And, you know, we're well known socialites, and this is the sort of atmosphere that barrel and her her, her good looking sister here Maisel grew up in. And if you go through the society notices that the paper you're always hearing about the balls, and you know what barrel was wearing, and maydel You know, and all this, you know, they were members of high society, this picture was taken around 1910. And a few years later, she was Botros to some dashing lift tenant and the Royal Navy. And it was a notice in the London illustrated, or like London, or whatever it is the major newspaper in London, you know, announcing the engagement, but nothing ever came of it. So So anyway, life went on. It's interesting, these young man here one of these, this young fella here died in World War One. Anyway, I won't get into all the particulars. So Richmond and during the course of their residents and tomatoes, they came into contact with a lot of native people because Gimenez, like a lot of rural BC towns, you know, there were large Native populations in the area. And, you know, the white population wasn't so large and so there's a lot of interaction. And Richmond during the course of his duties as a police constable would go to various native events. Now it's interesting. This is a photograph that Richmond took in about 1912 of a Potlatch chromogen. Now technically, the Potlatch was made illegal in 1884. But it was still being conducted and he was attending them. So there was some sort of, you know, negotiation going on between the local law enforcement and the Native people, which was kind of interesting because technically, this was all banned activity under the Indian Act, but it shows sort of the degree of cooperation and friendship that was that was shared between the town residents of chumminess and the native population. Okay, this is in the 20s showing. This is barrel here. And her family there's Richmond again and her mother, Gertrude and other family members, that's maple. There's her brother Frank, and her other brother Arthur. Now by this time, barrel, had married a local man, they bill crier, who who was a buddy of Frank's they both served in World War One together. And after returning from the war, barrel, married William crier in 1920, and they had one daughter, Rosemary. So they settled down to life and humaneness and barrel. And maple began to write stories for the couch and leader. And they were called legends of the cabochons. And they were very flowery kind of romanticized stories that were based sort of on the writings of Pauline Johnson. And they they had, you know, the goal of becoming famous writers, you know, of Indian lore. But they figured that the editor of the paper wasn't paying them much. So they gave up doing it, and tried to get these stories made into a book, they sent it off to various publishers, nobody was interested because, as you know, the depression was looming, and places like chumminess were particularly hit particularly hard. You know, it's lumber industry came to a standstill, and lots of people unemployed, and barrel managed to get work as sort of the social correspondent for The Times calling us the daily colonist just sort of wrote a weekly gossip column now who was getting married, who was doing what in Jamaica was, very exciting column. And then,

Speaker 1 17:12

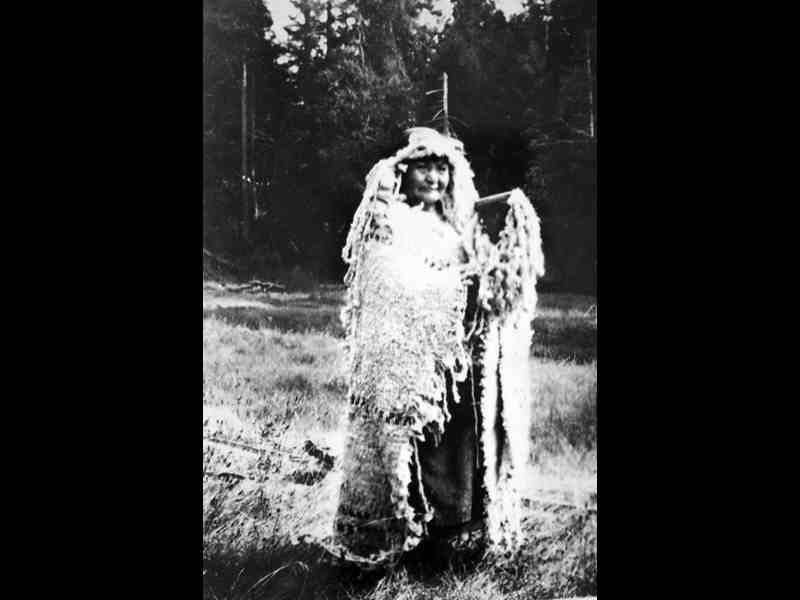

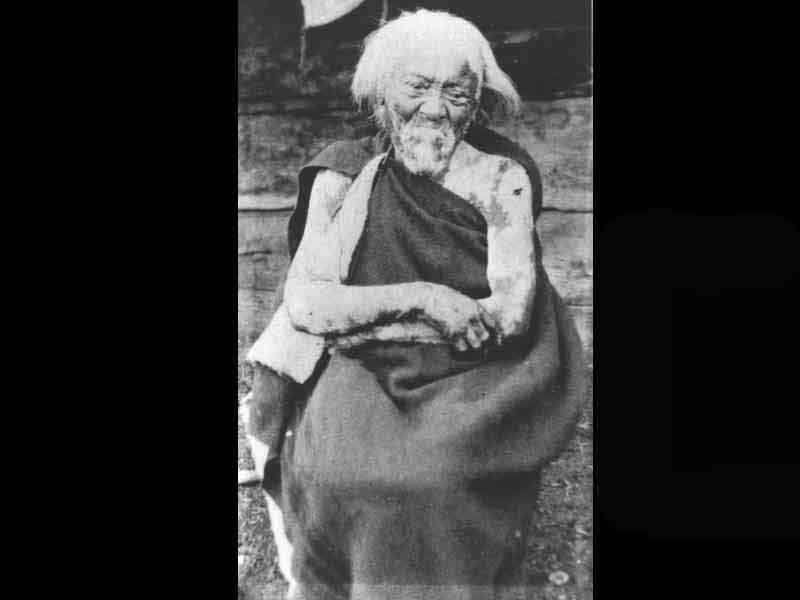

but but she took a lot of pride into it. And you know, even though it was a small column, he only got paid by the inch. So it provided some family income, and then all of a sudden, she was fired from the job. And as because the editor had given her position to somebody else. And she said, Well, how can you do that? She was really indignant and went off, you know, looking for the editor of the paper or the publisher, you know, and he just happened to be passing through chumminess, like, the day after she was can. And so she got ahold of him. And he said, Okay, you know, I promise we'll find you a position on the paper. She said, Oh, great. And then he went off to Nanaimo, and then he died. He had a heart attack or something. And so she said, Well, you know, that's it for my writing career. But lo and behold, she got a letter or some notification A few days later, or a few weeks later from the new editor and said, the dying wish of the publisher was the UV reinstated and self play to the daily call. And so he said, I'm here to offer you a job. Could you write maybe a weekly column or something or bi weekly column on Native Indian, Indian history for the paper? Because I think our readers would like it. This was Bruce McKelvey, who is the Assistant Editor. And some of you may have known Him or know Him as, as a sort of an amateur historian who, who did a lot of writing in the in the 30s and 40s. And so he encouraged her to write stories, which she did, she did, and that was the genesis of this book. Now, this is a photograph of Mary rice or Indian, it's holonomic. Now, Mary race, made the acquaintance of barrel prior years ago, Mary was born in Connecticut, in one of those long houses, on the beach, and from a noble family, it was a house of hardcore Collison. And she grew up in this noble family. And she married a man and they lived on the north end of Galliano for a while but he died in 1879 that she remarried another man in it in 1888 by the name of George rice, and George Weiss. Rice was half Irish, and half Swinomish. He was from the US. And so they settled together on rice Island, which is some of you may know is Norway, Ireland. It's a little island off of the off the coast of between Cooper Island and Galliano and they began to raise a family and they have four young children then George rice has a fishing he gets a massive heart attack falls in the water and drowns, leaving her with his four young children all under the age of 10. And because she had married this man who is technically a white man, according to the laws of the day, she was denied her Indian status. And so she was not able to live back on the reserve she couldn't live on on rice island. So she basically lived in a shack on the beach on humaneness with her four young children and went to work right away as doing whatever she could. And she began to build up a business as the village washer one Men. And so that's what she was known as in the early part of the 20th century and she means she was the village washer woman. She was also the village house, White House or midwife, and she delivered hundreds 1000s of babies during her lifetime. She, I talked to her granddaughter, Ellen White, some of you may know who said, Mary, I always used to tell her, you know, I've delivered 1000s of babies black, white, yellow, red, doesn't matter what color they are, they all come out the same. And so many of the early citizens of Jamaica so you know, who their lives to this woman's midwifery practices. She was also a healer, and a FISA, which is a woman who can see events in the future and events in the past, you know, and and had an incredible knowledge of herbal medicines. And she's also a cultural tradition bearers, she was a recognized authority on the cultural on the traditions of your tribe. And so she lived in the harbor chumminess for a while but after a while, she moved to a little shack right on the edge of the hall had property where barrel crier grew up. And so they they made an early acquaintance. And there's references in some of her stories about going down to the beach at night. And Mary would have a fire going she'd ever grandchildren around her and began just telling stories. Of course, the hall had girls were just fascinated by this. And you know, being, you know, sort of nieces or whatnot of Lord Baden Powell, they were very much involved in the Girl Scouts and all this stuff. So Mary's story is really stuck, or struck a nerve with the young women so fascinating as a depression. This was battle cry when she got this, this gig as a writer for The Times columnist, this was her informant, she immediately went to Mary rice, of course, Mary rice, and I got stories, I'll tell you stories. And the first five installments of this of her works. Were based on I'll just go forward here. This is all just before I get to their stories, this is a photo taken by barrel crier of Mary rice in wearing her smart cloth, which is a mound of blanket made a mountain goat wool, and this is only worn by the high ranking people. And she's holding her small squid sis, which is a special copper rattle it was only used by certain families. And so Mary, you know, obliges barrel crier with all these incredible stories and, you know, barrel wrote them down and submitted them to the paper. And at first, they only appeared in small little areas sort of scattered throughout the various during the week, but after a while they became they became so popular just within a month that they were, they appeared every second Sunday in the Sunday News Magazine, and were given quite a prominent place. And one of the most significant things about these stories from an anthropological point of view is that they're based from the perspective of a woman like her a lot of male anthropologists working in this area during the 30s. And a lot of them said, Oh, the old cultures dead, you know, we'll be lucky if we can grab any kind of remnants. And they worked exclusively with male informants, whereas the majority of the stories barrel crier collected are from the female perspective, they're collected from female informants, and to give a view of the woman's experience as a co Salish woman. But the first batch of stories that six or seven or more, were based on the stories of her grandfather, how colistin and how Collison has a lot of connections to Saltspring island. He is the granddaughter or that he was the grandfather or the father of a Lucy pizza and who married to Henry Samson. Little little Irwin is in here. This is your great, great grandfather. And so he is a patriarch of the Samson family, and his Indian name connects him to how Khalistan connects. That name is connected to Ganges harbour and Cooper Island and all kinds of different places. And this man This photo was taken in 1880s. He was almost 100 years old. He died a few years later. And you know, he was an infernal man. He suffered a lot from arthritis and frostbite that he had. He he suffered in his early days, but he was a notable warrior. Back in the day in the 1840s and 50s. This guy was one of the most feared powerful men at Connecticut, he actually led raids back he defeated Haida attacks on Cooper Island, and led raids back into the northern parts of Vancouver Island against people who were the enemies of the Panella. And so Mary rice, you know, grew up in his longhouse and was privy to a lot of his stories about his life and times, you know, from the early 19th century, and valuable stuff because, you know, no, nobody else collected any of this material However, it's not clicking here. Oh, here we go. For example, people like this. This was a man named from college, who was the chief at ko mocks. And one of the stories in here, it talks about a raid where Hulk Collison goes on a raid up to Quadra Island and get separated from the rest of his man, and has to make his way back on foot down on Vancouver Island through the British and he gets key, he finally makes it to Komatsu. He's assisted by this man who's shown here, this picture has probably taken an 1860s and he's wearing a top hat, which is was very common amongst the leaders of the the Coast Salish on the coast and they dressed in European clothing, you know, we have this sort of, you know, image that was that anthropologists like to give us some native people wearing bark and stuff. And I mean, they did wear that in the 18th century, but by the 1900s, most native people dressed like Europeans. Not everybody. Some people continued to just you know, wear blankets, this is a, an old couple of Talquin and tall clicked, a brother and sister who lived on the Cowichan river. And this was one of the another one of the stories that Mary rice gave barrel crier, this man here had the ability to charm fish in the river using his rattle. And one day, some people, you know, upset him. And so he used his rattle to draw the fish away from all the nets and weird and these guys couldn't catch any fish because this guy pulled them all in some areas using this rattle to charm the fish. He apparently had this ability. Other stories that Mary rice gave, you know, talks about the the Potlatch, the Stronach, which was a, you know, a great, they call it a party a good time, it's where people came to recognize ancestral names, marriages, the bestowing of ancestral names, particularly in a point to make here is about oral traditions like them, this is my book is called oral traditions and the whole community and in our culture, old traditions don't have a lot of cachet, people think of oral traditions, you know, there's, everybody's reminded that story, we put everybody in a room and you tell this guy over here, his story in the past that around the room, by the time it gets to this person, it's totally different. You know, that's, that's the white man's version, that would never happen in the native culture, any oral traditions, oral histories, they were all

Speaker 1 27:33

given in front of the community, they were not, you know, they were all validated by the community at at events like this, if this Potlatch may have been given to bestow an ancestral name on a child, and when that before that name was given, everybody be told about the name, the history of the name, the places where that name was associated with the rites and ceremonies associate with the name. And all the traditions would would be, you know, witnessed by everybody and understood by everybody. And so we tend to get a privilege, the written word, but oral traditions in this context, are just as strong, if not stronger. And anyway. But this is another there's a great account in there of a splenic by Mary rice, she also gave accounts of the SNAM, the Indian doctors, I was gonna read an account of the book, but I'll just keep going along here. You'll have to buy it, read it yourself. But they're excellent accounts. She claimed, you know, she said, our doctors know more than your doctors, and she gives a wonderful accounts and hear about a man who has a couple of gross bones stuck in his throat. And you know, he's choking to death, you know, and so they call a white doctor and the guy comes in, he's got metal tongs, and he's sticking them down the guy's throat, and, you know, causing these bones to get even more stuck. And so the guy's lying on the table, you know, and they're saying, Well, what he's done for he's gonna die. And then a woman comes in a snom, an Indian doctor, a female Indian doctor, who takes over and the white doctor says, What's this woman doing in here? And she says, I'll show you and, and there was a white man there saying, I'll bet you $10 That she can fix this guy. And the white doctor takes the bet. And of course, the Indian woman goes to work removes the bones through sucking, they had a technique where they would she sucked in the afflicted area and drew the bones out through the skin, and they could see the marks. It's all described in this book. And needless to say, the white doctor paid up and left quickly. But this picture, I originally didn't want this in the book because it was too old a photo this was taken from the 1860s. So this was a phenom from 1860. And of course, by 1930 the snobs wore the dress every day, you know, Canadians, you know, suits, ties, hats, that sort of thing. But they were they were and still are important members of the native communities in Duncan and Cooper Island guess any questions? Well, before while this little intermission no written language. No, there were just a few anthropologists that develop their own kind of writing system, but nothing,

Unknown Speaker 30:18

you know, consistent. Okay. So Mary also gave stories about the the origins or the the names associated with different villages. And here

Speaker 1 30:31

you will hear, I'll just show you a everybody I don't know if everybody knows, but really island off the coast off at the entrance of chumminess Harbor, used to have a large Indian village called cloth, which means painted houses. And it's not there anymore, the village people have moved now to the current cloth reserve, which you pass on the way to Duncan and an IMO. But this is a grave house on the village showing the type of grave house that they use in 1860s, with glass windows, and the bodies would lie inside. And there's accounts in here describing these houses. There's also detailed accounts of the native use of the land, this is a duck poll that was standing at the mouth of the chumminess River. In fact, there's Willie island here, and these are the flats at the mouth of the chumminess River, which you can see on if you're if you're vigilant on your way to the shininess. And these nets were incredible. They were maybe these poles are about, I don't know, 80 feet high. And they'd be you know, set at intervals along the flats, and a huge net would be strung up. They made of metal fiber. And they would string this up during the early hours of the morning while the ducks were kind of swimming around and you know, sleeping there. And then they would make a great noise and the ducks would fly up in the air and get caught in these huge nets. And then they lowered the nets, club the ducks and then process them and this way they would collect hundreds of ducks. And this just shows you the value of the stuff that she collected because nowhere have I read a more detailed account of of this kind of duck hunting technique. You know, I've read a lot of anthropology that was done in the 30s. But in here you get a very detailed description giving the names of the different parts of the nets and the pole and description of this very pole and this pole stood until recently down in chumminess.

Speaker 1 32:31

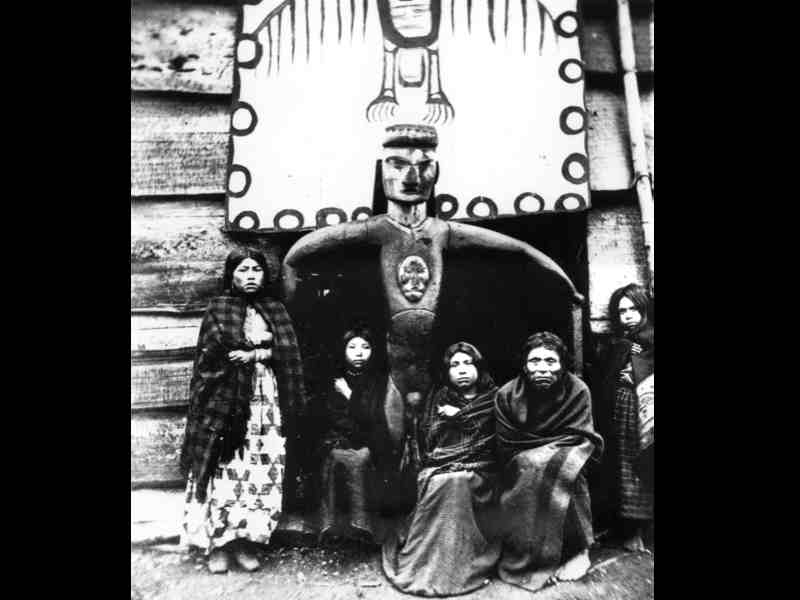

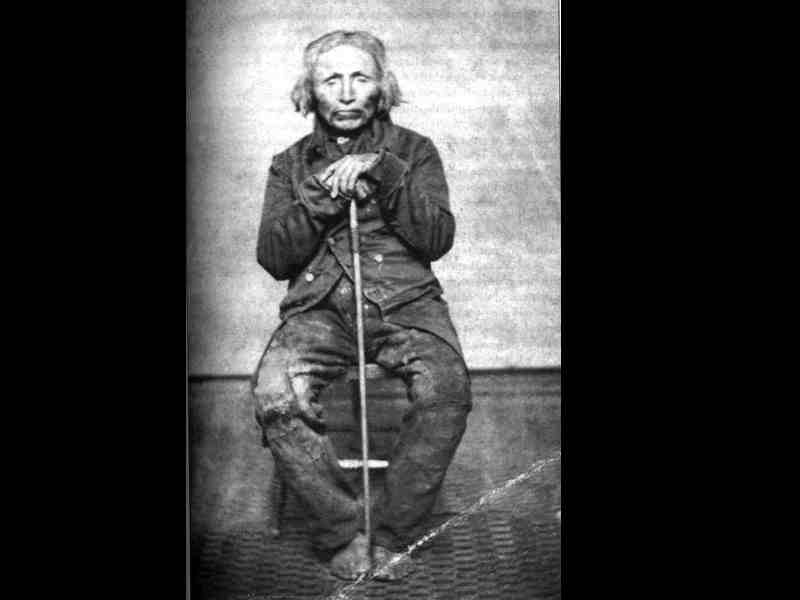

So Mary race contributed about half the stories in this in this book. There's about 60 stories in here. But after a while, she decided you know that that barrel needed to widen her group of informants. So she began sending her to various relatives of hers. And this is shows a group of this is taken in the 1930s. And many of these are some of the storytellers in the book are shown in this picture. This is Tommy PL who is the brother of Mary Rice, who contributes some stories. This is Jenny wise and Nanaimo. Her husband Joe wise, and these people down here off from Nanaimo. These ones are from Cooper Island. Now it's interesting, this man here, and this woman, we're from Salt Spring Island. This these are the poppin burgers. This guy his name is Sophia Aniston. And his wife, Keith, better known as Johnny pop and burger and Marianne Poffenberger. They lived at Beaver point. And she was a sister of Mary writes. So there's live connections to Saltspring Island, and there's references to Saltspring Island and some of the stories. So anyway, there was there was there was an agenda behind these, this this idea of Mary's to expand this, this group of informants because in 1927, the federal government forbade the any research into Indian land claims. And it was made illegal to do any kind of research that would promote, you know, non native awareness of of land ownership by Native people. And so I believe that these people seized on this chance to to have their stories told by a woman they trusted barrel crier, and even stated so in their stories when barrel crier first meets sadness then, so why is in Nanaimo gives us long speech, in the Nanaimo dialect. And it basically translates he says that he was saying, Thank you, white lady, for coming to visit me for so long. I've wanted to tell the white men what I know, but no one would listen, but she would listen. And so he and his wife Jenny, give a whole whack of stories about the Nanaimo beginning from the early origin histories of the tribe to various accounts in the 19th century. This is a great painting this was done in 1858 showing the the It was a follow up Hall, which stood in downtown Nanaimo, the Bastion, who would have stood around here. And these people moved, they signed a Douglas treaty. And in that treaty, they were obliged to move their village a few miles up to harbor so that the white man could build the mine, the first coal shaft was sunk right in the village of solok. Hall, here, and Joe wise gives an account of the finding of coal there and an account is a Douglas treaty, he was actually present at the signing of the Douglas treaty as a child. So it's an invaluable count of. Now this is a famous photograph that you see in practically every second history book of ISI. And these people have never been identified. But barrel crier and her stories through her interviews with Joe wise, you know, he's talking about this, this famous carving that his, his father had a commission, and it's this unusual carving here. We'll go to the next shot. This is an earlier photograph is one of the oldest photographs in British Columbia 1858. This was taken of that village we just saw in Nanaimo. And in the account in the book, there's no photograph, but Joe wise gives an account of this remarkable sculpture and his painting that was erected in the front of his father's house. And it's interesting in the same story, he asked her Oh, you know, I really wished you could find a picture of my father, I don't have any picture. But through her work, we've been finally able to identify, you know, photograph of his father, Mrs. Sadness, then with his daughter, in front of this remarkable piece of art that shows I won't get into story, but it shows the story is given in detail in the book. It shows the origin story of the softball Hall, those families that lived in Nanaimo, and it's illustrates a story about how they were born out of the sky and a huge thunder and lightning storm. And it's it's a great story that's detailed in the book. This is a picture of caskets and who is known as cold Tai Chi. He His claim to fame is that he was the one that attracted the white man to the incredibly rich coal deposits in Nanaimo. By visiting, he visited Victoria one day went to the blacksmith, and he saw the black since working with his coal and said, Oh, wow, there's tons of this down in Nanaimo. And so he went and showed the white man where it was. And of course, one thing led to another. And, you know, establishment of the coal mines, the incredibly rich coal mines in Nanaimo soon followed. So the story is about history in this book, Jenny wise gives an incredible account about the petroglyphs and Nanaimo. Many of you have probably seen Petrick Park, on the outskirts of Nanaimo. That place is known as talk when it was named after an Indian doctor who lived there and created these carvings which are known as halt a horse, which is the Indian name for writing. And in Indian language, they make no distinction between these pictures, and the writing system we use. And so it's a proto literacy that is showing here all these, these images relate to stories, many of which are lost, but some are still still known. I worked in a book in the early 1990s, where we worked with a native elder in the interior, a woman related to these people who could understand this form of a picture writing. Other informants that she met in Nanaimo girl crier she was introduced again through this family network, to this man here with James with a famous athlete of the day, his Indian name is quote, camels. And he was a well known athlete and an artist and also an authority on the history of his tribe. And he was unique for being a an artist. And he carved this with Chaka Chaka, which just means a carving and it's a totem pole. Now, the Coast Salish people did not carve totem poles, traditionally, the card house posts, which are about this size, but this is a poll that he did, because he was you know, by this time, they were familiar with a totem pole carving of the North. And so he wanted to do when, and this poll was raised in honor of his father top comment, and it's a poll that shows the origin of the Nanaimo people in this particular pool.

Unknown Speaker 39:36

It's not there, it's it stood for many years. I bet some of you remember this poll.

Speaker 1 39:43

If you came from the ferry terminal into Nanaimo is usually on the left there in front of a park, and stood for many years, and now it's lying in a decayed condition on the Nanaimo Indian reserve, but I do believe they're carving a replica of it. But I remember this poll, and I'm not that at all. Another famous informants of hers was John Peter, select select sulla of Northland Galliano, this man had a reputation amongst some of you may have, or I know some of you know of him may have even known him as children. He's lived to be over 100 years 100 years old 125 He claimed to be died in the late 40s. And he was an incredible cultural authority who was late related to Mary rice. And he gave her the lowdown on the the the Salish calendar, here's a great story in here where she, they'll try or gets in your head, she wants to learn about the Salish calendar, she hears about it, you know, the, the native people had a calendar that was based on the moons it was a lunar calendar, you know, depending on the moon came, they had a name for the moon, and the name of the moon usually was associated with a type of resource, or that was showing up at that time, like we've just gone through the month of Lima, Lima, which is refers to the lien which is the, which is the flight of geese. So it was the month when the geese appear. And sure enough, Leamas, the moon shows up and the geese start flying back up here. But John, Peter gave me the lowdown. And at the end of the story says write that in your newspaper and tell her that I told you this, this is the law as it came, or this is the the months of the Indian calendar as dictated by Indian law. So he was an authority, and he knew that these stories would be published, and wanted them published so that the white people would know. Although how many people remembered it, being in the newspaper that, you know, the ephemera, the newspaper, you know, the stories would appear in the weekend edition, people might read it disappear. So there are continued, you know, she worked in the news, these articles between 1932 and 35. And often it was, it was a lot of difficulty, because, you know, often the paper would run her stories, they wouldn't pay her the daily call, and it's almost went under, they had to fire most of their staff. And it's remarkable that she was one of the few colonists that they kept on. Even though you know, she often wouldn't get the money. Of course, she needed the money. And she was paid by the column inch. And which is you know, another one one benefit of that is that her stories are so long, they take up a whole page. And she didn't she didn't do any padding. And this, this was great, because what she would basically do or technique was to go in there, and just, you know, talk to the people of it. And it's always a beautiful description. And each one of these stories about, you know, usually visiting the person talking about events of the day. So you get a sense of what's going on in the 30s, you get descriptions of the people the homes they live in, and then they launch into the stories and she just let them roll, like a story from beginning to end. And the remarkable thing is, you get the complete stories, like Franz Boas who was a famous anthropologist who worked in this area 50 years earlier, and had no knowledge of the language and few people spoke English. And he communicated with his informants was Chinook. And so he got these tiny little fragments and stories, you know, very, like a paragraph or something barrel crier would get, like pages of stuff, the same story, but in way more detail with the names. And you know, she was amazing. She, she was very meticulous about recording Indian names, and, you know, very interested in, in authenticity. And you're very much aware of it, you know, she was a woman, she was not a scholar, you know, but she was from a family of scholars. You know, her one of her great, great uncles, you know, was a linguist who compiled dictionaries of Sanskrit. So she came, you know, she had a lot of this sort of family heritage that she had to live up to. But she was an amazing writer. And this is what have stirred my attention when I came across her writings. And this is a picture that I think she took, and here's her vehicle, her husband here, Bill would often have to drive her to remote areas where she would interview people, and often she would interview these people. And you know, it was just in time, like often or not often, but in several instances, these people died like a month or two later. And if she hadn't visited them got the story. We wouldn't have these detailed accounts. She could understand it, but she couldn't talk it. The fact is, she says so much in one of her letters, I was able to draw on quite a lot of correspondence that she made between between herself and William Newcomb, who was the curator at the DC museum. And she asked him for dictionaries and stuff, but it was nothing but but she had an ear for it. And when I wrote the book, or transcribed her the original text, I changed her transcriptions because she had her own way of writing the language but it wasn't consistent. You know? And so I worked with some informants of my own some native scholars like garbage, Charlie Florence, James Ellen White, who, who gate who showed me the proper way to write these names. So most of the names in the book are the current Rent transcriptions as understood by the native people. But she, you know, in that regard she was she was more meticulous than any of the anthropologists working in the day. There's another man that she wrote a story about, she visited the daughter of this man, this is a little cop, who figured prominently in the history of the couch and valley, in various military campaigns in the Cowichan. Valley, I won't get into the details, because they're in the book, but it's just another valuable. You want to know about the medal he's wearing there, and the uniform and even the crucifix, it's all explained in this book, through the words of his daughter. And it's interesting, because this man was probably the richest man amongst the Cowichan, in 1860s, up to the 1890s, when he died, but his daughter lived in poverty. You know, wealth wasn't sort of inherited, it was, you know, distributed. And, you know, there was no kind of hierarchy of rich people, it was all dependent on who you were at the time and, you know, your family connections, and yeah, no inherited wealth at all. And so her daughter, I was always complaining about that. She also gave a detailed account of the Swegway, mask, and the dance. And this is a Swegway Nast. The native people don't like these photographs, or published anymore. In fact, there's kind of a restriction against it. But this was carved by a white man. So I figured it's okay, and appeared in my book. And this was a man who visited or he was a well known, visited barrel crowd, because barrel crowd began to gain reputation as a cultural authority on the Coast Salish people by other leading anthropologists, in this case, George Emmons, who was a well known collector of Klingon art. And so he visited or when he was in his 80s, and he was really I want you to collect me some sway mass, I really like when here's what they look like, I had some guy make a copy of one. And so barrel crier showed this to Mary rice, and she immediately noticed recognize it as a fake. So what's this? Tell me this, and, you know, immediately recognized it as not being a native manufacturer. But there's a great account in there about the origins of the Swegway mask, and the traditions associated with it. And they're not secret traditions, I mean, they're, they're well known to people, but to get gain a proper understanding of it. Burial crier gets a great explanation in there through the words of the native people. And this is another thing about her work is that she didn't paraphrase anything. Unlike a lot of anthropologists, you know, the paraphrase. But the people tell him put it in their own words, not Barrow, like I said, you get paid by the colonists just let people go. And we're the beneficiaries of that, you know, methodology. Eventually, however, it kind of went against her. In 1935. She, she visited a Schmidt Club, which is the winter dance of the Coast Salish people. And it's, it's a secret of dance in the sense that it deals. It's only held during the wintertime. And it's a time when native people gain possession of the gardener of their spirits. And they actually have, you know, they congregate in the long houses, and all night long, and people get possessed by their spirits and perform dances is one woman explained to me we dance, who we are. And, you know, it's not uncommon for guests to be invited to this, she was actually invited to this performance. But she may have taken notes and recording equipment, and this is absolutely forbidden. And this was general knowledge at the time they were I have accounts from anthropologists who were forbidden to make any sort of recordings, or bring any kind of writing materials into the longhouse. And I have a feeling that this is what she did, because this was the last story that she wrote that had sort of a, you know, a native informant that was, you know, sort of contemporaneous with her position at the time, colonists. Immediately after this appeared in the paper, the story about the meatloaf, no one else would talk to her. And, you know, she, her stories continue to appear in the columnist for about another year and a half or so. But they were all older stories, some of which she had done with her daughter with her sister in the 20s. They weren't the same wasn't the body of work that she did from 1932 to 1935. So even though she had gained the confidence of all these people, there came a point where she crossed the line in in gaining her trust, or broke that trust. And she never wrote any more. She published one book that came out in 1949, a year after Mary writes, died, and it was a collection of the more sort of child or childish stories that she co wrote with her her sister back in the 20s. They're still very good stories in that they're

Speaker 1 49:42

authentic in the in the subject matter, but again, do the flowery kind of Pauline Johnson ish romanticize accounts that she wrote in the 20s None of the real, genuine kind of authentic material that she wrote for The Daily colonists in the three Please. But she continued her interest in native culture, she joined this organization, BC Indian and Arts Council, I believe it's name. It was mostly a group of mostly women that kind of promoted native arts and culture. And she continued to, you know, take pictures and, and collect information on Native people. Here she is shown in a law or she took his picture in the late 30s. There's her husband, Bill, and a friend inside one of the long houses that then standing at the original submenus on what is now better known as Cooley Bay, on Vancouver Island. a barrel crier. Her her husband died in the 60s. And then at an older age, and over the age, she moved back to Welland Canal to be with her daughter, rosemary, who had a family in Ontario. And she moved back there and she she didn't like well in. She said, she despised the place. And you know, wanted to move back to the coast, but but she was too old. And shortly before she died in the night, in 1980, she sent a copy of her all all of her columns that she had collected, she'd cut out of the colonists and take them on these pages. This foolscap and she sent them in this big pile, to the curator of the DC Museum, asking him if he would want if he could help her put it into a book. And of course, there's this big pile of stuff. And he said, and he read through it, and he wrote her back and said, You know, I'd love these stories, but I'll see what I can do. And he contacted Mitchell press, he actually did a bit of work, but nobody would take it on. And so he wrote back to her said, you know, I can't find anybody to make a book out of this. And she said, Well, I'm giving it to you. I give the copyrights throw it to the BC Museum, consign it to the incinerator, if you want, of course, he wrote back and said, you know, there's no way I'd have any, you know, I would never think of consigning it to the incinerator. Instead, it was, it was it was divided into three boxes and put into the BC provincial archives, and access only by a few scholars. And I came across your work in a master's thesis on the island place names of the How can alien, who was written in 1985, by a man named David Rosen, who did a lot of really good work, and introduced me to the language of the culture, and to her work. And when I found it, it was so important that I just spent the last 10 years slowly getting it together. And finally, it's about in the book, and I feel incredibly privileged to have been a part of getting barrel crier and her the people she worked with, you know, a greater audience, and thank you for your time. And thank you for coming out to this presentation.

Unknown Speaker 52:58

Any questions? I could ask them, yeah.

Speaker 1 53:08

I think she was, you know, just going on a pee. I mean, you know, I was wrong, and that she did write one more thing that came out in, I don't know, some of you may be familiar with the volume published by the tremendous historical society, in 1978 is called memories of the tremendous Valley. And because she was a, you know, from a pioneer family, and she made us they contacted her, and she wrote a wonderful biography on that, which I, you know, used quite extensively in my book, on the hall had family. And it's interesting in this whole book, there was nothing about the native history. In fact, the editor said, you know, we'll leave that to the natives, you know, we don't feel you know, confident to do their history. So that was just sort of all about the pioneers and stuff. But she, her contribution has a big chunk on Mary writes, because she said, I feel I have to mention, you know, this person because she was so important to the early days of shininess. But, and it's beautifully written I, you know, when you read the book, you'll see that, you know, what a gifted writer she was, I think she's incredibly talented. And that's what stands out. I mean, not only the content of the stories, but it's her literary ability that really captured mine and people who have read this you know, I'm all walks of life. You know, it really enjoyed her stories her accounts. But yeah, I think she could have done awesome thing. Yeah. Yeah, basically all cedar and basically a post and beam kind of thing. Infrastructure than planks, cedar planks on the outside, and it could all be dismantled, like all these buildings used to move the houses like they from the village here, that house there. I mean, that's a more of a modern long house, but in the old days, you'd be able to dismantle the whole thing, put it on two canoes, and ship it over to the Fraser River and rebuild your house. just Yeah. Yeah. Yeah, the was quite handy. Sort of uh

Speaker 1 55:18

oh, that they will the earliest plank houses on the coast. They figure the probably about a 2020 500 year old tradition. Because yeah, because you know, the cedar tree only got established around here around 5000 years ago. And this is when you see the beginnings of heavy woodworking tools in the archaeological record. So they figure well, once cedar trees are a certain size they're probably building big plank houses before that the people here lived in Pitt houses. Hey Charles

Speaker 1 55:54

Oh yeah, no Bob. Yeah, grand grandchild. Yeah. He helps me with some of the stuff in his book. Awesome guy very knowledgeable man.

Unknown Speaker 56:05

Oh, yeah, he's a guy I got to interview more because India yeah

Unknown Speaker 56:26

yeah yeah, I do know Bobby's cool guy.

Unknown Speaker 56:30

Yeah,