Before, during and after the years following World War II, Japanese Canadians were almost always referred to as ‘the Japanese’ and those who were uprooted were often called ‘the Japanese evacuees’. Despite being either naturalized or Canadian-born citizens their property was taken from them. How could this happen in a country that prides itself in operating under the rule of law?

When the Custodian’s right to forcibly sell Japanese Canadian property was challenged in the Iwasaki case, in his Reasons for Judgment Justice Sheppard explained that when the property was vested with the Custodian he acquired ‘all the rights of the enemy’, but added, ‘(here evacuee)’. This is interesting because it shows that a law written to cover the property of enemies was being applied to the property of a different group of people, evacuees.

The Japanese Canadians uprooted from the ‘protected area’ were never referred to as enemies. The action was almost always referred to as an ‘evacuation’, a euphemism implying that it was at least partly intended for the protection of the people being uprooted. Framing the uprooting of Japanese Canadians as an ‘evacuation’ was essential to the process; the government would have faced much greater resistance from Japanese Canadians had it been perceived as ‘detention’, and the uprooting process would likely have looked more like it did in the United States where Japanese Americans were held behind barbed wire. By referring to it as ‘evacuation’, the government was more likely to get the compliance of the people being ‘evacuated’ and they would be less likely to resist the vesting of their property. For the public, if the internment of Japanese Canadians had been seen as ‘detention’, the government’s actions would have looked disturbingly similar to those of Nazi Germany, with which Canada was fighting a fierce war for freedom and democracy.

Sheppard’s use of the term ‘evacuee’ in a paragraph explaining the legality of liquidating their property prompts us to consider if the government really had the legal authority to sell off the property of Canadian citizens who were ‘evacuees’ and never legally defined as enemies.

During World War Two, the War Measures Act gave the government unrestrained power to enact whatever regulations it felt it needed, and under the Act, Orders in Council from the Cabinet had the same legal force as legislation passed by Parliament. It is commonly believed that the War Measures Act ‘allows the government to do whatever it wants’ and in a sense it does because it can pass whatever regulations it likes without the restraint and oversight of Parliament. But the Act doesn’t suspend the rule of law; regulations need to be made and adhered to, and everything done to the Japanese Canadians was carried out under the legal authority of Orders in Council and Regulations.

In trying to understand how Canadian ‘evacuees’ came to be treated by the government as enemies and have their property taken from them, it is useful to review the chain of legal steps that enabled it to happen.

All subsequent Regulations and Orders in Council were enacted under the authority granted to the government under the War Measures Act 1914 (amended 1927)

Under the War Measures Act the Cabinet (referred to as the Governor in Council) was given the power to enact laws without debate and a vote in Parliament.

3. The Governor in Council may do and authorize such acts and things, and make from time to time such orders and regulations, as he may by reason of the existence of real or apprehended war, invasion or insurrection deem necessary or advisable for the security, defence, peace, order and welfare of Canada;

This included:

3. (f) Appropriation, control, forfeiture and disposition of property and of the use thereof.

And these orders and regulations shall have the force of law:

2. All orders and regulations made under this section shall have the force of law, and shall be enforced in such manner and by such courts, officers and authorities as the Governor in Council may prescribe, and may be varied, extended or revoked by any subsequent order or regulation;

Under the Act, the government enacted an Order in Council to create a set of regulations under which it will operate during the war:

2. Order in Council 5295 – 15 July 1941 – Defence of Canada Regulations 1941

‘Persons of the Japanese race’ were required to register as such under Order in Council 9760:

3. Order in Council 9760 – Registration – 16 December 1941

It enacted an Order in Council that amended Regulation 4 of the Defence of Canada Regulations to give itself the power to declare a protected area:

4. Order in Council 365 – ‘Protected Area’ - 16 January 1942

Shortly afterwards another Order in Council further amended the Defence of Canada Regulations to give the government the power to require people to leave the protected area:

5. Order in Council 1486 – Expulsion – 2 February 1942

Order in Council 365 amending Regulation 4 did not refer specifically to Japanese Canadians ; this changed with Order-in-Council 1486, and shortly after it was enacted, notices appeared requiring ‘persons of Japanese racial origin’ to leave the protected area.

rescinding paragraph 2 of Regulation 4 thereof and substituting therefor the following paragraph:

(2) The Minister of Justice may, with respect to .a protected area, make orders in relation to any of the following matters:—

(a) To require any or all persons to leave such protected area;

Now detained under the Defence of Canada Regulations, under the ‘Revised Regulations Respecting Trading with the Enemy (1943)’, the Japanese Canadians could have been defined as enemies. Regulation 1.(d)(ix) states, ‘“Enemy” shall extend to and include– (v) Any person who has been detained under the Defence of Canada Regulations during the period of such detention;’ So defined as enemies, their property could have been taken from them and held by the Custodian who, under of the Trading with the Enemy regulations, could have done whatever he liked with the property, and the original owners would have no right to challenge the dispossession. This might have given the government sufficient legal authority to liquidate Japanese Canadian property, but it would have been conceding that the ‘evacuation’ was ‘detention’. In any case, the regulation was not applied and the government took a different route.

21. (1) All property in Canada belonging to enemies at or subsequent to the commencement of the present war, and whether or not such property has been disclosed to the Custodian as required by these Regulations, is hereby vested in and subject to the control of the Custodian.

(2) This regulation shall be a vesting order and shall confer upon the Custodian all the rights of such enemies, including the power of dealing with such property in such manner, as he may in his sole discretion decide.

22. (1) No enemy whose property is vested in the Custodian under these Regulations shall have any rights or remedies against any person in respect of any such property after such vesting has taken place.

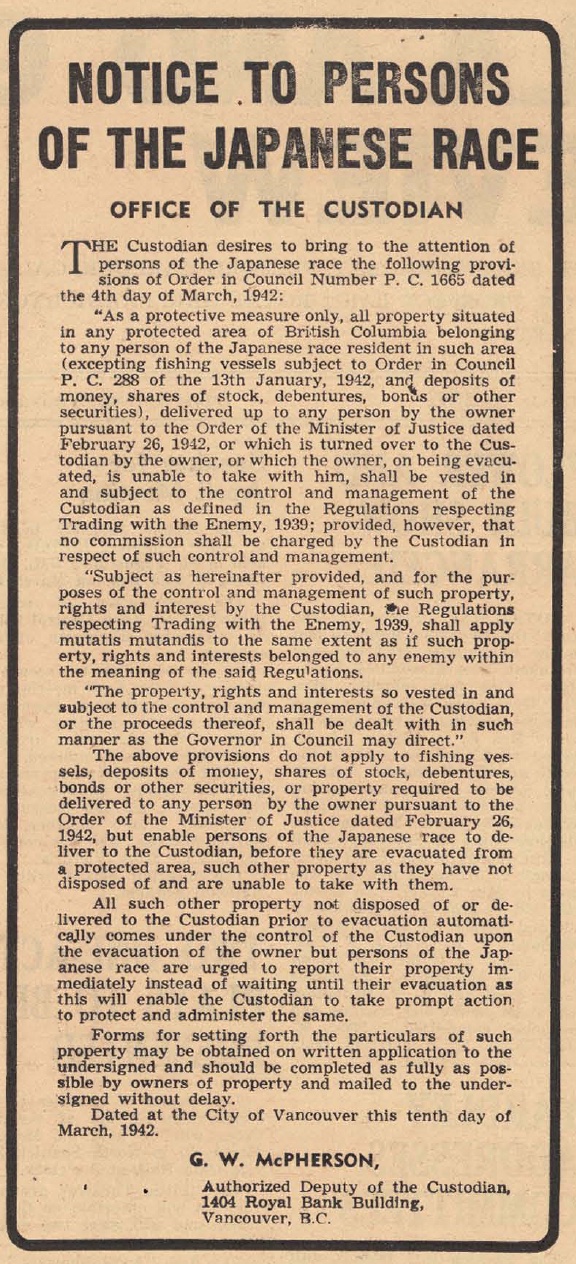

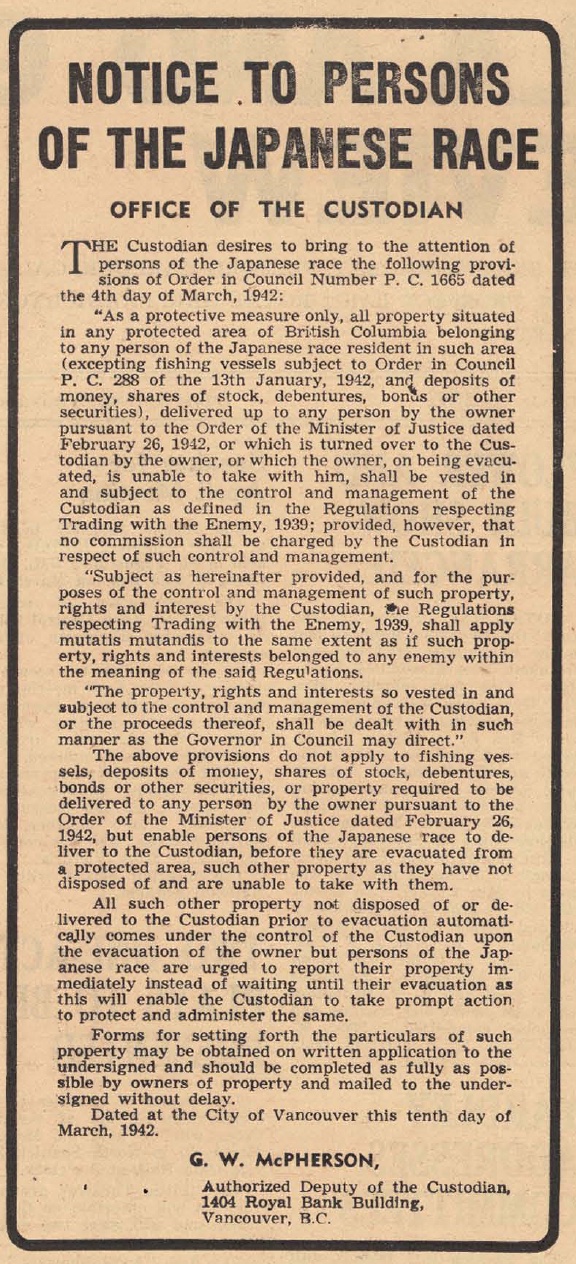

‘Persons of the Japanese race’ resident in the protected area were ordered to vest their property with the Custodian:

6. Order in Council 1665 – Vesting of Property – 4 March 1942

Section 12 (2) of the order stipulates that the property will be treated as though it belonged to an enemy, ‘…the Regulations respecting Trading with the Enemy, 1939, shall apply mutatis mutandis to the same extent as if such property, rights and interests belonged to any enemy within the meaning of the said Regulations.’

Custody of Japanese Property

12.

(2) Subject as hereinafter provided, and for the purposes of the control and management of such property, rights and interest by the Custodian, the Regulations respecting Trading with the Enemy, 1939, shall apply mutatis mutandis to the same extent as if such property, rights and interests belonged to any enemy within the meaning of the said Regulations.

Order in Council 1665 was later amended by Order in Council 2483 , which defined a ‘person of the Japanese race’ as anybody required to leave the protected area under the Defence of Canada Regulations.

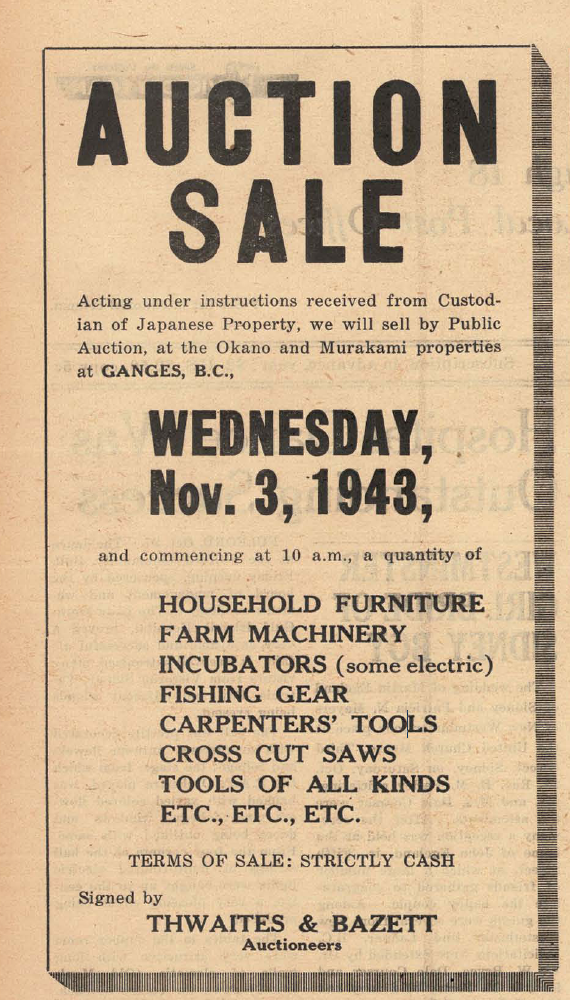

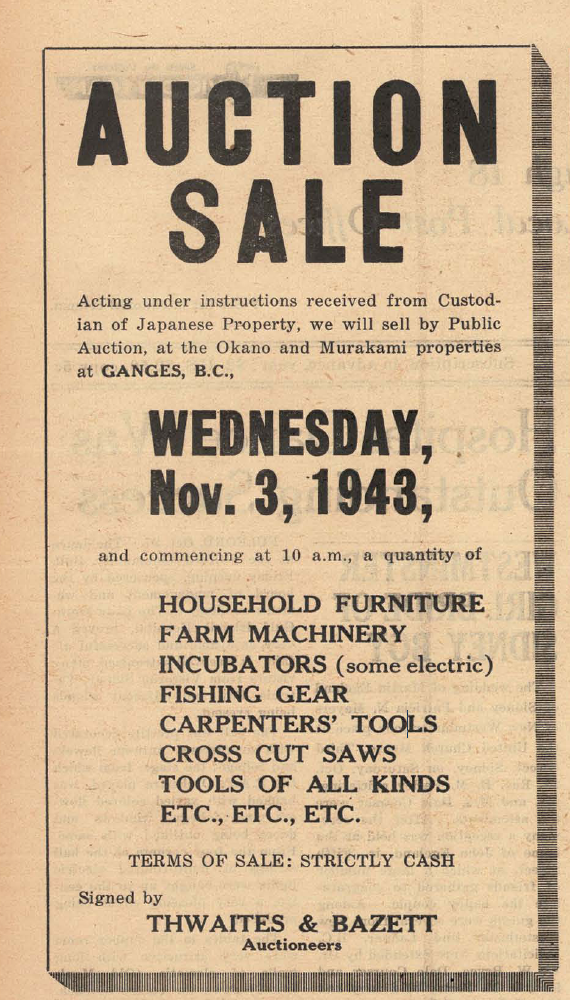

Finally, an Order in Council was passed to amend the Trading with the Enemy regulations to give the Custodian the power to liquidate vested property, applying the regulations as though the ‘evacuees’ were enemies:

7. Order in Council 469 – Liquidation of Property – 19 January 1943

Issued under the authority of the War Measures Act, the order stated the ‘power and responsibility shall be deemed to include and to have included from the date of the vesting of such property in the Custodian, the power to liquidate, sell, or otherwise dispose of such property.’5 Acknowledging that this order was being applied to people who were not the enemy per se, it concluded with the clarification that the sales would proceed as though the property belonged to an enemy: ‘…and for the purpose of such liquidation, sale or other disposition the Consolidated Regulations Respecting Trading with the Enemy (1939) shall apply mutatis mutandis as if the property belonged to an enemy within the meaning of the said Consolidated Regulations.’6 [emphasis added]

The forced sale of Japanese Canadian property during World War II offends a sense of natural justice, but the legal challenges to the dispossession (Nakashima v. The King , Iwasaki v. The Queen ) failed because under the War Measures Act, the government could make whatever orders and regulations it chose without having to answer to Parliament or the citizens of the country. Looking for some chink in this formidable armour is likely futile, yet with the benefit of hindsight and access to internal government documents unavailable to earlier researchers, one cannot help but speculate on possible lines of attack on the actions of the Canadian government during the war.

Were there not rights to property that superseded the power given to the Governor in Council under the War Measures Act to expropriate property from Canadian citizens? Under the Constitution Act, 1867, property rights are within provincial jurisdiction in Canada, but the War Measures Act temporarily transferred that jurisdiction to the federal government. In any case, British Columbia didn’t have a property law until 1996. Federally, there was no change to property rights under the Canadian Bill of Rights, 1960, or after the Charter of Rights and Freedoms was enacted in 1982. It has been suggested that property rights should be added to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In 1991, the Canadian government issued a paper on the proposal, ‘Property Rights and the Constitution’ , but nothing further has been done on it. Thus, at the time of the dispossession of Japanese Canadian property and to the present there never has been constitutional protection of property rights in Canada, only common law protection, and all of that was suspended by Section 3 (f) of the War Measures Act which gives the Governor in Council the power to enact Orders in Council that allow for the ‘appropriation, control, forfeiture and disposition of property and of the use thereof’.3

While that would seem to be unchallengeable, the beginning of Section 3 of the Act states, ‘The Governor in Council may do and authorize such acts and things, and make from time to time such orders and regulations, as he may by reason of the existence of real or apprehended war, invasion or insurrection deem necessary or advisable for the security, defence, peace, order and welfare of Canada.’4 [emphasis added] The important word here might be ‘deem’, since just about anything the government did could be ‘deemed’ to be for the welfare of the country, yet Order in Council 469, as the justification for the liquidation of Japanese property does not state that the action was being carried out for any of those reasons; i.e., ‘the security, defence, peace, order and welfare of Canada’, it only stated that the liquidation of the property was necessary because ‘…the evacuation of persons of the Japanese race from the protected areas has now been substantially completed…’5, none of those things.

But Order in Council 469 has a more fundamental weakness: it was calling for the application of a regulation within the Consolidated Regulations Respecting Trading with the Enemy against a group of people who haven’t been defined as an enemy. In his ruling on the Iwasaki case, Justice Sheppard felt the need to include ‘(here evacuee)’ after the word ‘enemy’ when citing the powers given to the Custodian under the Consolidated Regulations because the regulations apply to enemies and not evacuees. Was Order in Council 469 as written sufficient to allow the government to allow a regulation that applies to enemies also to be used against people who do not fall under the legal definition of an enemy?

In Nakashima v. The King and Iwasaki v. R the judges ruled that the government could apply a law for dealing with the property of enemies against people who were not enemies. Order in Council 469 states that the Japanese Canadian property will be liquidated ‘mutatis mutandis as if the property belonged to an enemy’. ‘Mutatis mutandis’ means ‘the necessary changes having been made’, but 469 is far more than the application of a law to slightly different group of people or in a slightly different way–what changes are necessary when applying a law written to deal with the property of enemies when it is being applied to people who are not enemies?

Order in Council 469 was different than the other orders in council that were enacted to govern the uprooting of Japanese Canadians. Rather than creating regulations or amending existing ones, it seeks the application of existing regulations to a different group of people.

The War Measures Act gave the government the power to seize and liquidate the property of enemies, but the word ‘enemy’ was strictly defined in the Consolidated Regulations. (It is not defined in the War Measures Act.) The closest the ‘evacuees’ could have come to being defined as ‘enemy’ under the Consolidated Regulations is in Section 1. (b) (v) where an enemy is defined as: ‘Any person who has been detained under the Defence of Canada Regulations during the period of such detention.’ The Japanese Canadians were detained, although that could be challenged because that was not how the government defined what it was doing when it uprooted them; it was an ‘evacuation’. Part (iv) gives the government even greater power; an enemy can be, ‘Any person who is declared by the Governor in Council to be an enemy’, but that never happened. Neither of these provisions was applied to the Japanese Canadians, and Section 1. (b) also states, ‘Provided, however, that Enemy shall not include any person only that he is an enemy subject’, and the people to whom this action was being taken were not even enemy subjects, they were Canadians.1

Why didn’t the government simply use Section 1. (b) (iv) and classify Japanese Canadians as enemies in order to liquidate their property? Likely because that would have been perceived by many, including those not particularly sympathetic to the Japanese Canadians, as being a step too far, and too similar to the actions of the authoritarian regimes with which the country was at war.

The War Measures Act gives the government sweeping powers to act in a time of war, but it doesn’t suspend the rule of law, it just changes how laws and regulations are made. It eliminates the need for laws to be debated and passed in Parliament. It allows the government to essentially make laws by decree, which is what it did in the creation of the ‘Consolidated Regulations Respecting Trading with the Enemy’ and the ‘Defence of Canada Regulations’, and then it is expected to operate within those regulations. Order in Council 469 orders the liquidation of Japanese Canadian property ‘as if the property belonged to an enemy within the meaning of the said Consolidated Regulations’1 [emphasis added], but that exceeds the scope of the Consolidated Regulations–it was ultra vires–there is no provision within them for the liquidation of the property of people who are not enemies.

Thus, Order in Council 469 was not valid, the government acted illegally.

War Measures Act 1914 (amended 1927)

Order-in-Council 5295 – 15 July 1941 - authorizing the Defence of Canada Regulations 1941

Order-in-Council 9760 - Registration of ‘Persons of the Japanese Race'- 27 December 1941

Order in Council 365 – ‘Protected Area’ - 16 January 1942

Order in Council 1486 – Expulsion – 2 February 1942

Order in Council 1665 – Vesting of Property – 4 March 1942

Order in Council 469 – Liquidation of Property – 19 January 1943